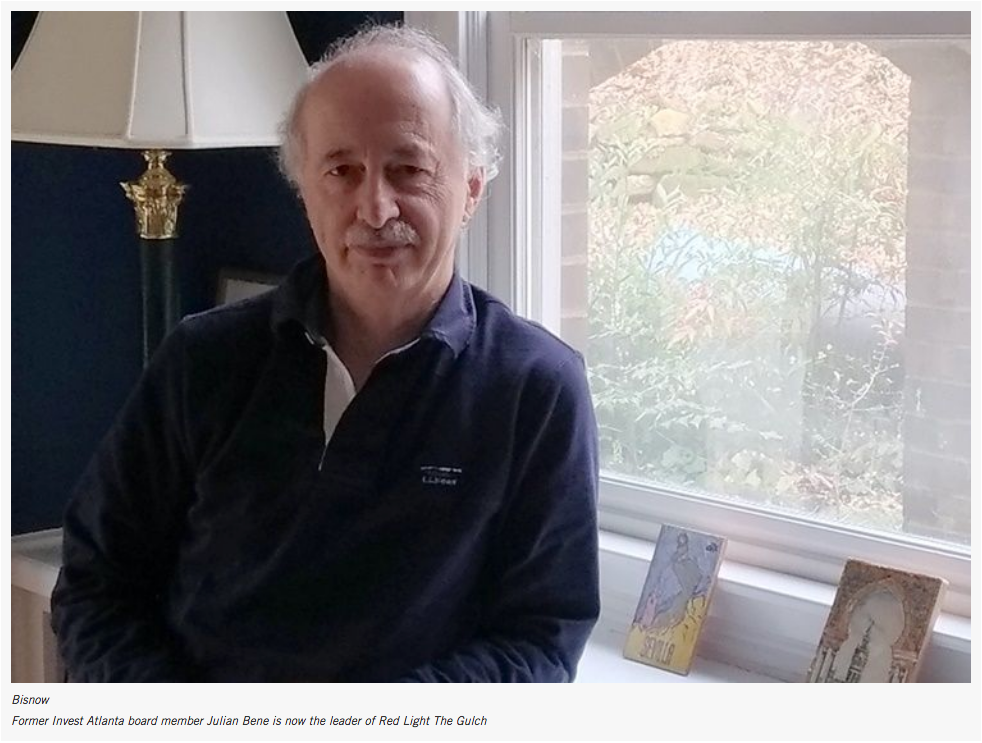

For eight years, Julian Bene sat on the board of Invest Atlanta, which approves tax breaks for developers in the city.

Bene was often a lone dissenting voice during his time on the board. But now he is taking on a more prominent role: the leader of a new, populist surge of resistance against local government incentives for private developers.

“Even the economic development that I was supporting was not translating into more tax revenues to help more residents out,” Bene said. “That became my ‘a-ha moment’ a year before I left.”

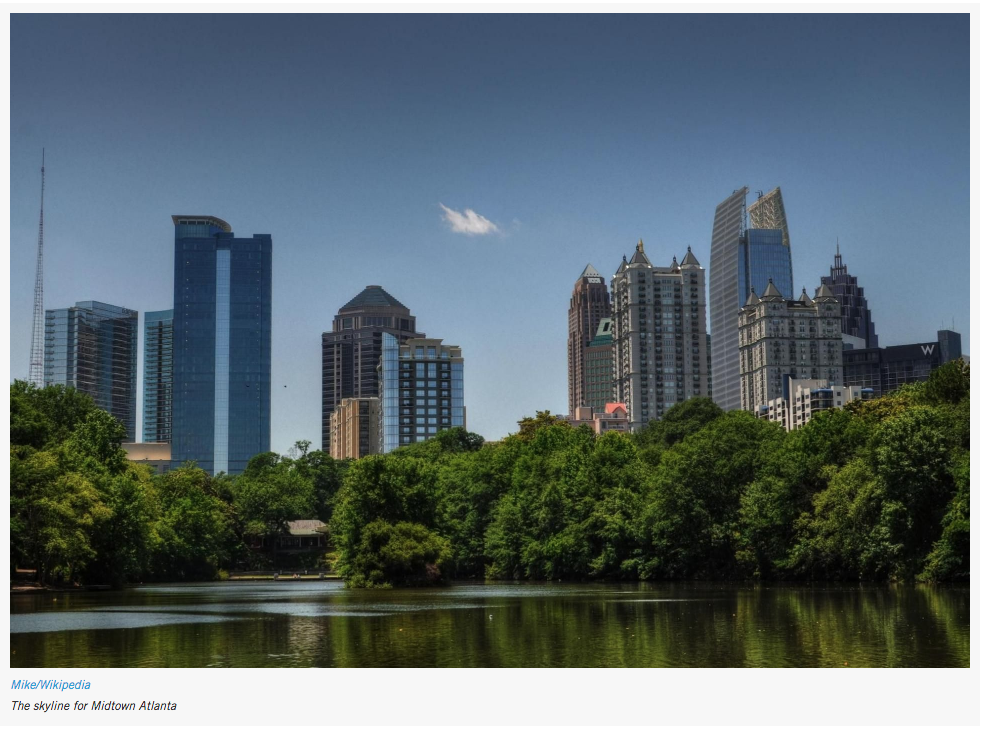

Since the end of the Great Recession, Atlanta has boomed. The city’s population grew from 422,800 to more than 486,000between 2010 and 2017, with thousands of new apartments to house them.

The office market has taken off with it, with the equivalent of nearly five Bank of America towers — the tallest office building in the Southeast — being added to the market, filled with marquee names like NCR, Anthem Healthcare and Worldpay.

During that time, city and county officials have regularly granted developers incentives to encourage the building of all kinds of commercial projects — from mid-rise apartment buildings to distribution facilities to corporate giants’ gleaming new Midtown office towers.

But as Atlanta faces a worsening affordable housing crunch and continues to reckon with some of the country’s worst congestion, critics of the incentives, which largely come in the form of tax breaks, are starting to get louder.

Proponents of incentives say they produce tremendous economic impact. Tax abatements offered through Invest Atlanta, according to Atlanta’s annual financial report, generated more than $310M in revenue in 2018 along with the creation of 205 jobs and 860 housing units.

Because of the positives associated with new development, almost every project that applies for a tax incentive in Atlanta receives approval, industry experts say. And most projects apply for a tax break.

“Many cities around the country have given incentives away on projects that probably don’t need them,” said David Wilson, vice president at development firm Ryan Cos. “Many developments have gotten through, and people haven’t batted an eye.”

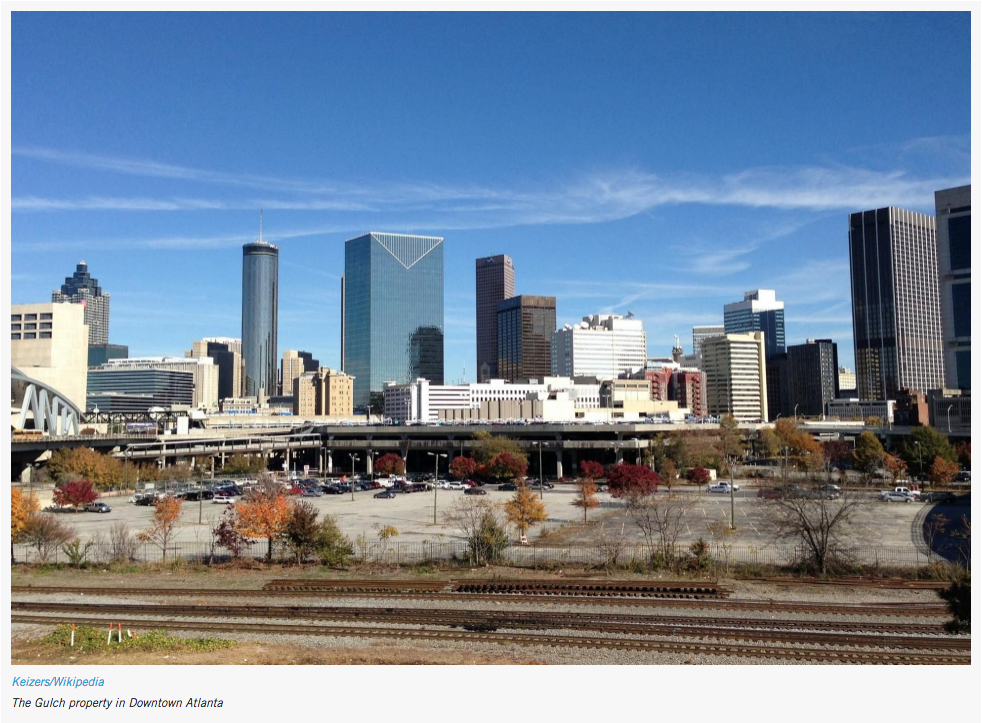

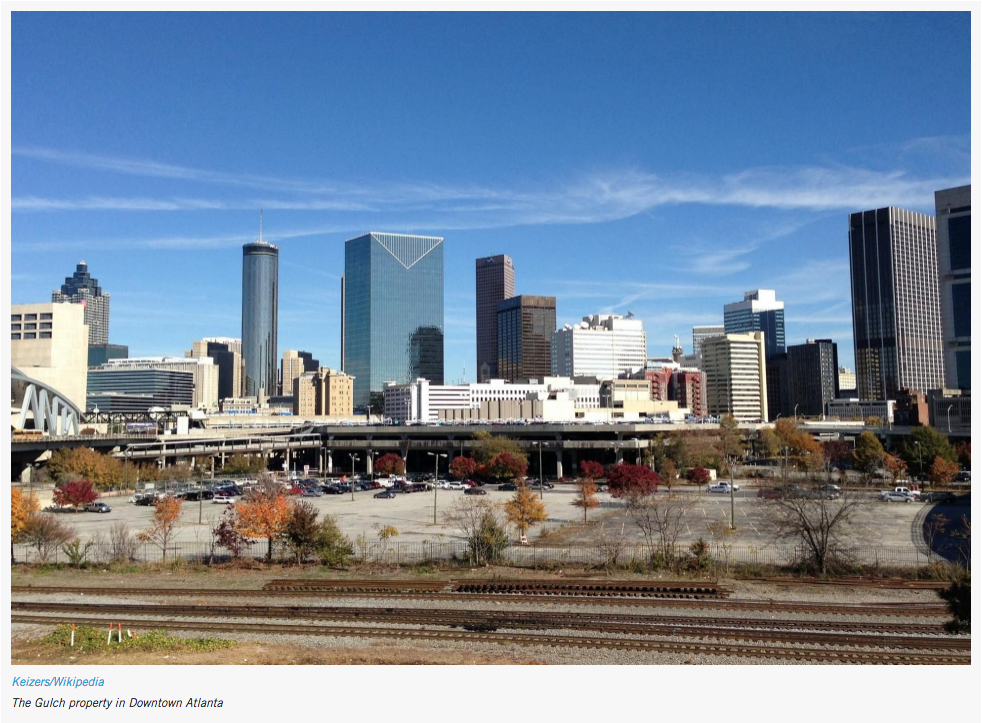

Since leaving Invest Atlanta last year, Bene has spearheaded a group fighting against the biggest incentive package ever devised for private development in Atlanta: $1.9B to redevelop a sea of asphalt and rail lines in Downtown Atlanta, called the Gulch, into 9M SF of office, 1M SF of retail, 2,100 apartment units and 1,500 hotel rooms. The package of tax breaks was approved in November, but not until Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms had to push back several votes and make last-minute concessions to win over a skeptical City Council.

Bene’s group, Red Light The Gulch, organized speakers to loudly protest the incentive package, mounting some of the staunchest development opposition in the city’s history.

“I’m a dangerous guy to have around,” Bene said. “So far, they haven’t found a way to get to me.”

The Incentive Game

Economic development incentives were created to help communities. They can entice developers to build in neighborhoods that may be neglected, or take a chance on reviving neighborhood eyesores, by helping to offset an owner’s risk.

Developers don’t get a blank check from governments — supporters of incentives contend property tax breaks are simply bequeathing a portion of future property tax revenues generated by the new development to offset the costs for building it.

Without the new project, tax revenues on the property would remain lower than they would without the infusion of new businesses, retail sales and the rise in the property’s overall value.

There are also rising land and construction costs to consider, and regulatory hurdles that have to be overcome. Incentives can be key to get projects off the ground by helping justify those costs, Fuqua Development principal Jeff Fuqua said.

“Nobody is writing a check. You have to produce the development,” Fuqua said. “If you don’t create that, then there’s no money. A lot of people think it’s corporate welfare, but it’s not at all. You have to produce a huge amount of activity to really benefit.”

Projects in some of the hottest markets in Atlanta — like Midtown and Buckhead, where companies and residents continue to flock for all the accoutrements of urban life — don’t necessarily need incentives to get built, opponents maintain, and they still put pressure on infrastructure and government services.

“A lot of times these tax abatements are going to projects in areas where assistance doesn’t seem like it’s needed,” Atlanta City Councilman Amir Farokhi said. “Even within my own district, I see this. Midtown is a high-demand area, and we continue to see various sorts of tax abatements going there.”

The Rise Of The Backlash

While the granting of incentives has largely gone unnoticed by most of the general public for years, that changed last year, not just in Atlanta but across the country, thanks in large part to Amazon’s hunt for a second headquarters location.

Governments all over North America offered lucrative and appealing incentives — like tax breaks, land and even cash — to lure the online retail giant to their region. Critics say tax abatements, while effective in attracting employers and developers, have real consequences for municipalities across the country.

Massachusetts-based think tank Lincoln Institute of Land Policy estimated in 2012 that cities and counties across the country lose anywhere from $5B to $10B annually in forgone property tax revenues. In the years since that study has come out, the arms race to lure jobs has only increased.

Atlanta City Council President Felicia Moore said this awareness and backlash toward incentives has been rising since well before the Gulch vote.

“You saw it all sort of explode with the Gulch,” Moore said. “People felt like the companies were either here already and weren’t going anywhere, or [already] had the financial wherewithal.”

Moore said there is a growing idea among residents in the city that whatever jobs are being created are not being filled by local residents, further exacerbating resentment.

“Jobs are always touted as a reason, but there’s never been a direct — at least in the public’s mind — tie between the jobs that are available and them getting the jobs,” she said.

During his time at Invest Atlanta, Bene investigated the impact of three issues that he says are draining city, county and school coffers: property tax abatements and tax allocation districts on the Eastside and Westside; sales tax stagnation; and commercial real estate values that have been chronically under-assessed.

Abatements alone cost the city of Atlanta, Fulton County and Fulton County schools as much as $40M a year in lost revenues, Bene wrote. The Eastside and Westside tax allocation districts, another popular form of incentives, generated a loss of $28M annually, he said.

“If we had no abatements, I would say that there would probably be no change in the amount of office and luxury apartments that got built,” Bene said.

He conceded that perhaps they would not be as elaborate or on such a grand scale in some cases, but they would have moved forward nonetheless because of Atlanta’s huge, and growing, demand.

“Yeah, we’d be better off,” he said.

Bene was among the many citizens who came before the Atlanta City Council to lodge their protests against the Gulch deal. In the months since, Bene has solidified that into his Red Light The Gulch organization. While the new group continues to battle in courts over the Gulch deal, Bene is using it as a vehicle to fight other big incentive packages in the city.

Protests against incentives for big projects are not relegated to Atlanta. A populist uprising against so-called “corporate welfare” — led by Democratic Socialist Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, alongside a group of local politicians — was a reason why Amazon decided to pull the plug on plans for a portion of its second headquarters in Long Island City, New York.

Farokhi, who was elected to Atlanta City Council in 2017, said more and more, the public is asking worthy questions when it comes to public incentives. Does a project create a public benefit that improves their lives? Do the projects getting incentives fit into their community’s overall vision? Are public incentives needed where market demand is already high?

“We’re not quite reconciling all three of those things,” he said. “To a lot of people, the answer appears to be no.”

Farokhi represents District 2 in Atlanta, which includes some of the city’s hottest neighborhoods: Midtown, the Old Fourth Ward, Inman Park and portions of Downtown. Farokhi was one of six council members who voted against portions of the Gulch incentive package.

CCIM Institute Chief Economist KC Conway said one reason for the widespread pushback has been the Great Recession itself. When the economy sank, there were cuts to public services and infrastructure left neglected as municipalities struggled with shrinking budgets.

What’s more property taxes are the lifeblood of public school systems. On average, public school systems receive anywhere from 65% to 80% of their budgets from the taxes property owners shell out every year, Conway said. So while developers have been incentivized with tax breaks to push new developments, Conway said many residents saw a stagnation in schools or in infrastructure improvements.

“Every chance we have to potentially benefit from development, you take it away and give it to the developer for 10 years,” Conway said. “The local community is saying, ‘Wait a minute. We’re not seeing our schools improve.’ They get all upset, and they get involved in the political process and bring things to a halt.”

Moore, who won a runoff election for council president in 2017, said Atlanta’s various TADs account for 16% of the city’s overall debt. That could spell trouble for the its budget in the next recession.

“If we don’t start looking at … closing [some TADs] and start addressing tax revenue directly, we don’t have any other ways to raise tax revenue,” other than raising property taxes on homeowners, which would be hugely unpopular, she said.

When It Works

Developers and economic development officials say a project’s success takes patience, especially when it is transforming an underused piece of property or an underserved community.

“If, in fact, you don’t have incentives, why would developers come to areas in need of redevelopment?” Dentons partner Steve Labovitz said.

Even in hot submarkets in Atlanta like Midtown and Buckhead, some developers say they need incentives just to be competitive. Land costs and construction costs have skyrocketed. If a developer building one property got an incentive, then it would be an unfair advantage to not give one to another being built nearby, Labovitz said.

“It’s always a balancing test,” he said. “It’s not clear-cut either way.”

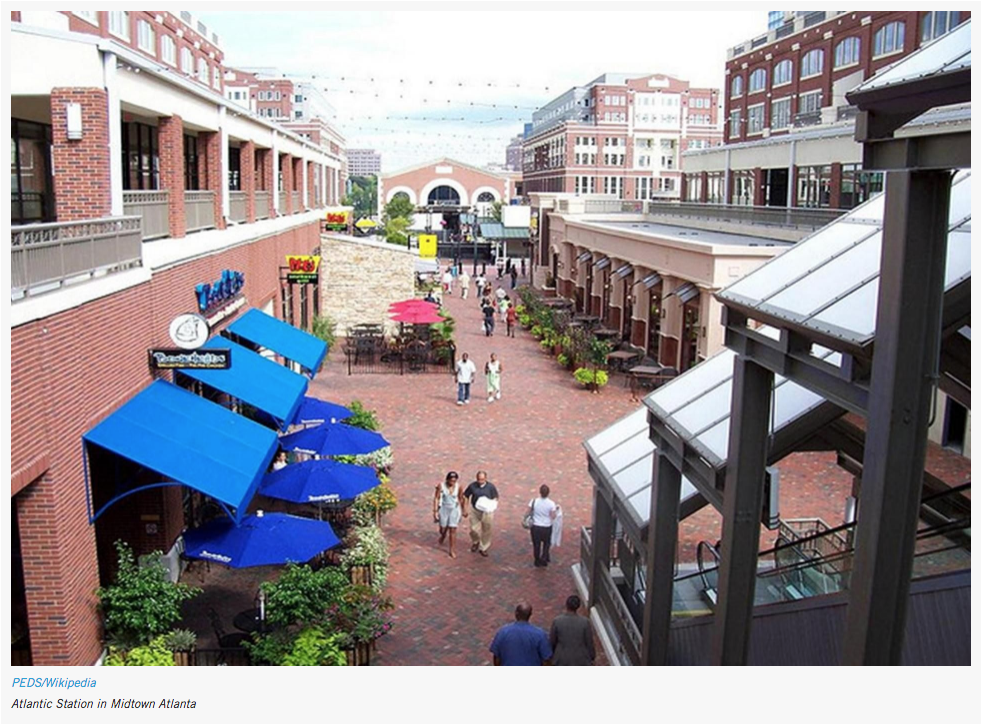

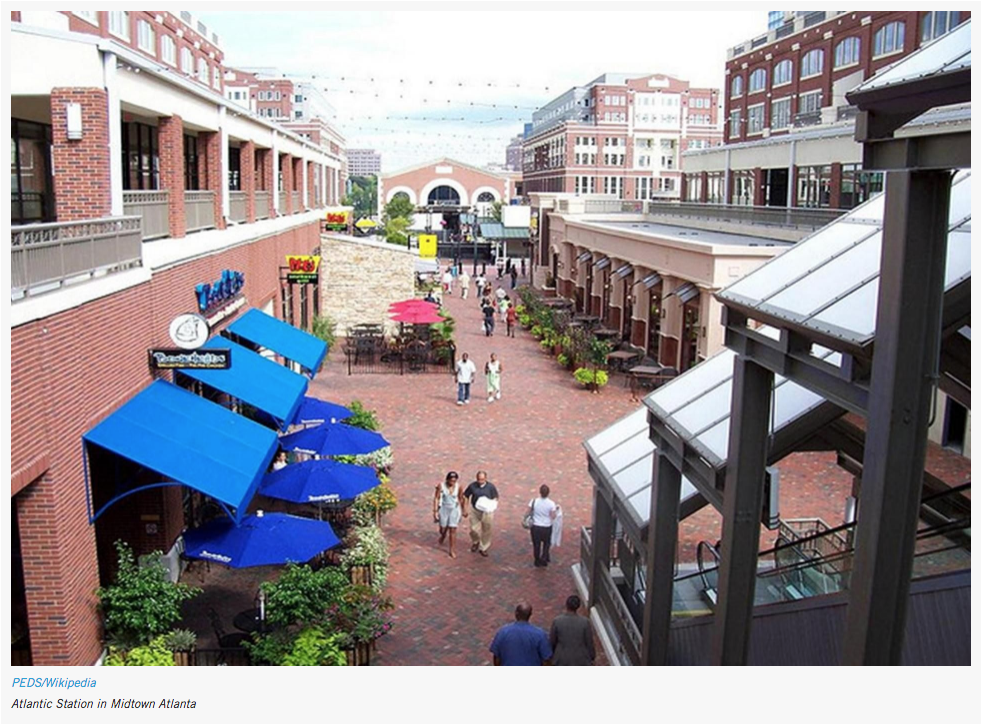

One of the city’s premier developments, Atlantic Station, was the beneficiary of incentives before a single tower ever rose. Advocates for incentives say it represents a great example of how the tax breaks can be used to have a long-term impact beyond the initial incentives.

The mini-city in Midtown Atlanta sits on what was once a plot of land that was contaminated by its former life as a heavy industrial site. Today, Atlantic Station is home to office towers, apartments and prominent retail.

The developer, Jacoby Development, and its partner, AIG Global Real Estate Investment Corp., spent $250M on removing those contaminants from the soil after they purchased it in 1999. In exchange, the developer got the benefit of $170M in TAD financing on the project. Last year, Jacoby CEO Jim Jacoby told the Atlanta Business Chronicle that there was no way that project would have happened without the TAD.

Jacoby and AIG sold the development in 2011, and pieces of it have traded hands since. But the TAD bonds, which had an outstanding balance of $195.6M as of August, mature Dec. 1, 2024.

Before Atlantic Station, the 138-acre parcel generated $365K in property taxes a year, Jacoby said. Today, property taxes alone are now $30M a year, on top of the $40M in sales tax revenue it generates.

“From $365K to $70M — is that a good story or what?” Jacoby said.

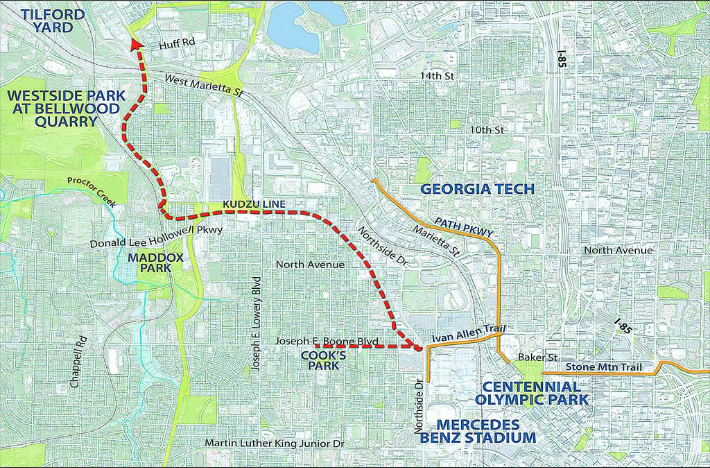

Atlantic Station has become the catalyst for the growth of Atlanta’s Westside, today one of the hottest areas in the entire region. That’s the ultimate goal for the Gulch for Downtown Atlanta, despite the contention, Labovitz said.

It will take time to see its impact, but city officials calculated that Atlanta will make back multiples of the $1.9B it is giving up.

“There is a backlash, I think, [with] big projects and the amount of money [they receive] because they take a lot of time,” Labovitz said. “Thirty years from now when the Gulch is built out, people may be saying, ‘This is the greatest thing since sliced bread.’”

By: Jarred Schenke – Bisnow

March 4, 2019

Link to original article

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16330052/MidtownHotelBar.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16330055/MidtownHotelLounge.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16330053/MidtownHotelLobby.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16330056/Woof.jpg)